城端蒔絵について

About Jōhana Makie

- Since 1575 -

城端蒔絵のはじまり

The Beginnings of Jōhana Maki-e

小原家は、第五十九代「宇多天皇」の第八皇子「敦實親王」を祖とする近江源氏・佐々木氏の流れを汲む。文明7年(1475)、本願寺八世 蓮如が越前から加賀・越中へと赴く際に、近江源氏・佐々木高範の裔で、越前朝倉義景の家臣であった佐々木入道祐玄が随身して、砺波郡梅原村(南砺市梅原)に来て定住した。祐玄は文亀年間(1501-1504)に80余歳で没したが、その曾孫佐々木又兵衛之綱が天正元年(1573)、23歳のときに城端へ移住し、同3年(1575)に大工町で髹工(塗師屋)を家業として塗師屋又兵衛と名乗り、「城端塗」の基礎をきずいた。これが小原家における塗師としての元祖であり、城端漆工のはじまりでもある。

その頃、南朝の遺臣 畑六郎左衛門時能の裔で、佐々木氏とも一族である畑治五右衛門好永という漆工が城端近郊の大鋸屋村に住んでいた。好永は天正年間(1573-1592)に肥前長崎で唐人から「彩漆密陀絵法(いろうるしみつだえほう)」を学び、城端に伝え「城端蒔絵」の基礎をきずいた。

好永はその技法を息子の二代 治五右衛門宜安に伝えた。しかし宜安は後に医師に転じたので、塗師屋又兵衛の孫の三代 徳左衛門信好に密陀絵法を伝授した。承応3年(1654)、信好37歳のときである。これより信好は、自家伝来の髹漆の技法に彩漆密陀絵法を加えてさらに研鑽を積み、白蒔絵の特色をつくって多くの作品を制作した。

加賀藩五代藩主 前田綱紀が、当時諸国名工の最高水準の技法を集めた「百工比照」という技術資料がある(東京駒場・前田育徳会蔵)。そのなかに、五十嵐道甫・椎原市太夫らとともに、治五右衛門の城端塗があげられていることは、当時の城端蒔絵の水準の高さを示すものである。これは信好の作品ではないかと推定されている。

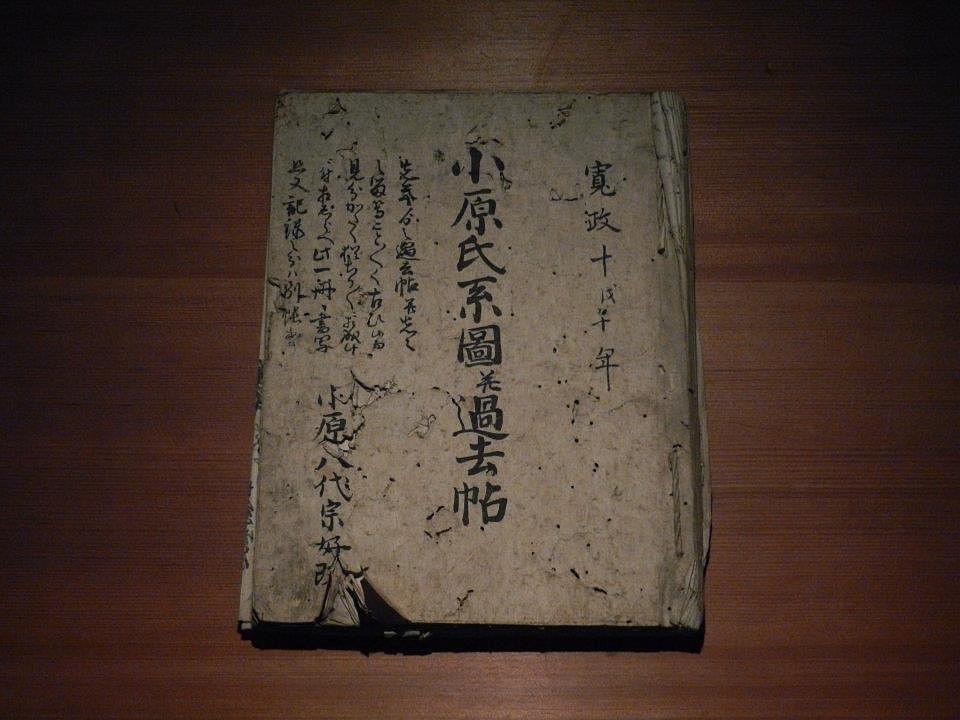

信好の長男、四代 理右衛門亮好は従来の家名「佐々木」を廃して「小原」と改姓し、六代 治五右衛門忠好以降、代々「小原治五右衛門」を襲名している。

The Ohara family descended from the Omi-Genji and Sasaki clan, whose ancestor was “Imperial Prince Atsumi,'' the eighth prince of the 59th “Emperor Uda''. In the year 1475, when Rennyo, the 8th head-priest of the Hongan-ji Temple travelled from Echizen (present day Northern Fukui Prefecture) to Kaga (Southern Ishikawa Prefecture) and Etchu (Toyama Prefecture), he was attended by a vassal of the Echizen warlord Yoshikage Asakura, Nyudo Yugen Sasaki, descendant of Takanori Sasaki, a member of the Omi-Genji clan. Nyudo Yugen settled down in a village called Umehara in the Tonami District (present day Umehara, Nanto city, Toyama Prefecture), and passed away at the age of 80 some time between 1501 to 1504. His great-grandson Yukitsuna Matabei Sasaki moved to Jōhana in 1573 at the age of 23, starting the family lacquering business in Daikumachi town, adopting the name Matabei the Lacquerer, thus the foundation of “Jōhana Lacquering” was built. This became the origin of the Ohara’s family lacquer trade tradition, and marks the beginning of Jōhana Lacquering.

At that time, an urushi lacquerer from another branch of the Sasaki clan, HATA Jigoemon (Yoshinaga), lived in the Village of Ogaya near Jōhana. A descendant of HATA Rokurozaemon (Tokiyoshi), who served the Southern Court in the previous civil war, Yoshinaga learnt the art of “Multi-Coloured Mitsuda-e” from Tang Dynasty Chinese in Nagasaki, Hizen ( present day Saga and Nagasaki Prefectures),some time during the Tensho period (1573 to 1592). By bringing such techniques to the Jōhana area, he played an important role in building the foundation of Jōhana Maki-e.

The techniques of Yoshinaga were succeeded by his son, HATA Jigoemon II (Gian). Gian later became a medical doctor, however, and taught those techniques to the grandson of Matabei the Lacquerer, Nobuyoshi Tokuzaemon, the third successor of the family in 1654, when Nobuyoshi was 37 years of age. Nobuyoshi combined the traditional lacquering techniques of his family with the Multi-Coloured Mitsuda-e techniques, and after much diligent effort, he developed the characteristic white maki-e, creating many wonderful pieces.

The fifth lord of Kaga, Tsunanori Maeda, compiled an encyclopaedia of crafts, “A Comparison of One Hundred Crafts” (Maeda Ikutokukai Collection, Komaba, Tokyo), recording in its pages the most skillful craftsmen and their most famous arts from all corners of the country. Listed among renowned artists such as Doho Igarashi and Ichidayu Shiihara was the Jōhana Lacquering of Jigoemon, indicating the superb quality of Jōhana Maki-e at the time. The works featured in the encyclopaedia are thought to be creations by Nobuyoshi.

Sukeyoshi Riemon, the fourth successor and the eldest son of Nobuyoshi, discarded the old family name of Sasaki and replaced it with Ohara. From the sixth successor, Tadayoshi Jigoemon, the name of “Jigoemon Ohara” has been passed down from generation to generation.

城端蒔絵の特色

The Characteristics of Jōhana Maki-e

城端蒔絵は「城端塗」または「治五右衛門塗」とも呼ばれ、美術工藝界に特異な存在として知られており、一般の蒔絵とは趣を異にする。

元来、漆で発色することのできるのは、朱・黒・黄・緑・茶の五彩に限られ、白を発色することは不可能とされていた。城端蒔絵はこの白色を表すことを特色とし、花鳥文様などを描いて生態そのままの色調ぼかしを表現する彩漆蒔絵技術を一子相伝の秘法として今日まで伝えるものである。これには、初期の作品に多く見られる「密陀絵法」と、それを基にしてさらに工夫を加え創出された、中期以降の作品に多く見られる「白蒔絵法」とがある。

蒔絵とは本来、漆で文様を描きその上に金銀の粉を蒔き付ける技法であるが、加賀藩では加賀蒔絵保護のため藩外での金銀の使用を禁じた。豪奢な加賀蒔絵に対して、城端蒔絵は白をはじめ各種の色彩を自由に駆使し、瀟洒で雅味のある独特の様式を案出したものである。

Also known as Jōhana Lacquering or Jigoemon Lacquering, Jōhana Maki-e is a unique curiosity in the world of fine and applied arts, and completely different from conventional maki-e.

In regular maki-e, only the five colours of red black, yellow, green and brown can be developed from the lacquering, and it was deemed impossible for the colour white to be formed. Jōhana Maki-e, however, characteristically makes use of the colour white, developed using secret techniques for multi-coloured maki-e passed down from a single line of succession, and its availability makes a wide variety of colour shadings possible when drawing wildlife and nature and other scenery. This technique combines the litharge techniques seen in the early works of the family, and through much research and hard work based on those techniques, it became the “White Maki-e” seen in works some time around the middle of the line of succession.

Originally, maki-e is an artform where gold and silver powder is sprinkled on patterns drawn with lacquer, but the warlord of Kaga prohibited the use of gold and silver outside of his feudal domain in order to protect the local Kaga Maki-e. In contrast to the extravagant Kaga Maki-e, Jōhana Maki-e uses a variety of colours made possible by the white lacquer, creating unique illustrations that are vivacious yet elegant.

城端蒔絵の展開と継承

Development and Heritage of Jōhana Maki-e

《初期》

密陀絵という呼称は、顔料を練り合わす油に密陀僧(一酸化鉛)を混入するため名付けられたもので、東洋における油絵の先駆的なものである。古代に中国から伝わり、我が国では正倉院に数多く収蔵されている作品からみて、密陀絵の手法が奈良時代に盛んであったことがわかる。しかし、平安以後は密陀絵の作品を作るものがいなくなり、長らく衰退していたが、畑治五右衛門好永が城端に伝え、復活させたのである。

密陀絵は「唐法描漆」、「光彩描漆」とも称し、初期の作品に多い。柴田是眞が愛蔵した「鳳凰桐蒔絵軸盆」(東京藝術大学蔵)は、昭和4年(1929)平凡社発行の「世界美術全集」にカラーで所載された。

《中期》

初期の「唐風様式」から、六代 治五右衛門忠好の頃に白蒔絵法による「和風様式」へと展開し、これを完成させたのが七代 治五右衛門林好(稀雄)である。その好例として、白蒔絵と金蒔絵を併用した高岡市勝興寺の「勝興寺宝物」の一品に、「松桜に千鳥文見台」(富山県指定文化財)がある。これは加賀前田家から拝領したものと伝えられ、城端蒔絵が加賀藩からの御用があったことを裏付ける。また、林好の作で、乾漆の手法による蒔絵を施さない黒漆塗の「桔梗形乾漆椀」10客(南砺市指定文化財)は、城端塗の代表作の一つである。

林好の後は、その子の八代 治五右衛門宗好(一白)、九代 治五右衛門房好(雄蔵)の兄弟に受け継がれていくが、この頃は城端蒔絵の最隆盛期であって、それぞれの精進努力と旺盛な研究により、白蒔絵の技術はさらに進歩し、蒔絵の題材も多様化して巧みな意匠構成をした。宗好の代表作「鶏に花籠蒔絵硯箱」(南砺市指定文化財)は、絞漆を用いた銭目塗という特異な塗りの上に、鶏と菊を精巧華麗に表現している。

また、蘭学・天文・暦象・測量など西洋学問を習得した宗好は、文化9年(1812)に「渾天儀」(南砺市指定文化財)を制作する。「亜細亜人一白」と銘が入っているところに、宗好の自信のほどがうかがえる。

房好は家伝の技法に斬新な感覚で新風を吹き込んだ。天保8年(1837)の作「彩漆鯰模様手付盃盆」(富山県指定文化財)は、ちり・むら一つとどめぬ豪快な塗り立ての上に、二匹の鯰を大胆な構図で描き、白い腹が鮮やかに浮かび上がる生命感あふれる作品である。これは小原家一子相伝の白蒔絵の特色を表す代表作の一つで、世上に「治五右衛門の白鯰」と賞賛され、各皇族も御覧になった由緒ある作品である。

《中期以降現代》

廃藩置県によって、従来、大名や富豪の庇護を受けていた世の漆工家たちはその職を失い、古い伝統を誇った各系統や各流派が崩壊消滅していった。城端では幕末から明治にかけて、十代 治五右衛門、十一代 治五右衛門(得賀)、十二代 治五右衛門(白晁)が出て、城端蒔絵の伝統を守った。

十代 治五右衛門は蒔絵のほか、仏壇塗の名手で、先代からの「治五右衛門仏壇」という伝統様式を守った。諸家にはその遺作が現存する。

得賀は一層精巧緻密な作品を残した。慶応元年(1865)作、「花鳥文九ツ組乾漆盃」は、絵画的にも優れ、優雅で美しい。「花鳥文料紙箱」(東京国立博物館蔵)は、金蒔絵・螺鈿を交えて、精細な技術で華麗な表現を行っている。

白晁は、優れた作品を数多く制作し、しばしば展覧会などに出品した。主なものとして、明治21年(1888)京都開催連合共進会、同27年(1894)第4回内国勧業博覧会、同34年(1901)仏国巴里万国大博覧会(パリ)、同37年(1904)聖路易万国博覧会(セントルイス)などでそれぞれ受賞した。晩年金沢に移住する。

十三代 為治は白晁より蒔絵を学んだが、大正14年(1925)に京都市へ移住し、刺繍を業としたため、城端蒔絵は一時中絶する。

十四代 治五右衛門(白照)は途絶えかけた城端蒔絵を再興するため、京都市立美術工芸学校で漆工を学び、江馬長閑に京蒔絵を師事する。昭和22年(1947)城端に戻り、天覧品を制作したのが復活第一作となる。翌23年(1948)の第4回日展に「鴛鴦模様手筥」が入選し、城端蒔絵が健在であることを示した。白照は、従来城端蒔絵に見られなかった題材も取り入れ、新しい表現分野を開拓した。また、城端・八尾の曳山御神像の文化財修復や、歴代遺作展の開催など伝統の保持にも努めた。白照没後、十五代 治五右衛門(好博)に続き、現在は十六代 治五右衛門(好喬)が継承している。

城端蒔絵は天平の密陀絵の再現にはじまり、それに基づき白蒔絵法を編み出し、各代の造形感覚により創意工夫を加え、小原家一子相伝として継承されてきた。明治維新の改変や戦後の変動期にも絶えることなく今日まで伝統のあかりを守っている。工藝の分野では極めて特異な例である。

【参考文献】

「治五右衛門と城端蒔絵 」洲崎哲二編 (城端文化協會)

城端町の歴史と文化 (城端町教育委員会)

Early Works

The name Mitsuda-e or lacquering comes from the method of mixing litharge (lead monoxide) into the oil that combines with the paint. It is the precursor of oil painting in the east. Originally from China, it was a very popular technique during the Nara Period, as seen in the vast collection of works in Shosoin of Japan. However, after the Heian Period Mitsuda-e faded out from art history for a long time, and it was only until HATA Jigoemon (Yoshinaga) brought the technique to Jōhana that enabled its revival.

Mitsuda-e were also called “Tang lacquering” or “glaze lacquering”, and were frequently seen in the earlier works. The “Phoenix and Paulownia Maki-e Scroll Tray” a favorite collection of Zeshin Shibata (owned by Tokyo University of the Arts collection) was included in the “Complete Works of World Arts” published by Heibonsha in 1929.

Middle Ages

From the Tang Chinese style of the early period, the Jigoemon VI (Tadayoshi) began working towards a Japanese style white maki-e, and such development was completed by his successor, Jigoemon VII (Shigeyoshi). One fine example of such work would be the “Pine, Cherry Blossom and Thousand Bird Stand” (designated cultural property of Toyama Prefecture); cherished as one of the “treasures of Shokoji Temple” in Takaoka, it is a work of art combining white and gold maki-e. This piece is said to had been in the possession of House Maeda, Lord of Kaga, and a proof that Jōhana Maki-e were reserved for feudal lords of Kaga. Another series of works representative of Jōhana Lacquering are the 10 pieces that comprise the “Balloon Flower Dry Lacquer Bowls”(designated cultural property of Nanto, Toyama), created by Shigeyoshi using black dry lacquer without any maki-e.

After Shigeyoshi, the brothers Jigoemon VIII (Muneyoshi) and Jigoemon IX (Fusayoshi) succeeded and improved upon the white maki-e techniques, which brought about a period of prosperity for Jōhana Maki-e, with the creation of maki-e artwork with diverse themes and various delicate craftsmanship. The definitive work of Muneyoshi, "Rooster and Flower Cage Maki-e Ink Box”(designated cultural property of Nanto, Toyama) was created using an unusual technique of applying strain lacquer “coin hole” style, exquisitely and elegantly portraying the rooster and chrysanthemum.

Furthermore, Muneyoshi was also a student of many western disciplines such as Dutch studies, astronomy, surveying and so on, which culminated in his creation of an armillary sphere (designated cultural property of Nanto, Toyama) in 1812. The armillary sphere is marked with the inscription, “by Ippaku (Muneyoshi’s nickname), an Asian”, a sure sign of Muneyoshi’s pride and confidence.

Fusayoshi brought ground-breaking innovations to the traditional techniques of the family. In 1837, he created the “Multi-Coloured Catfish Pattern Serving Tray with Handle” (designated cultural property of Toyama Prefecture), which consisted of no-buff lacquering without even the slightest blemish, where two catfish were drawn in a bold composition, the vivid white of their bellies seemingly radiating with vitality. This is one of the most symbolic works of the Ohara family demonstrating their white maki-e, a trade secret strictly kept within the single line of succession. Known as “the white catfish of Jigoemon”, this prestigious work of art has been displayed in front of many members of the imperial family of Japan.

From the Middle Ages to Modern Times

During the times of the abolishment of the feudal domains, many lacquerers previously under the patronage of feudal lords or magnates were out of work, their traditional bodies of techniques with long histories vanished in the mists of time. Fortunately, Jigoemon X, Jigoemon XI (Tokuga) and Jigoemon XII (Hakucho) were successful in defending the Jōhana Maki-e tradition from the end of the shogunate through the Meiji Period.

Apart from his skills in maki-e, Jigoemon X was also a famed lacquerer of Buddhist altars, and he kept up the family tradition in his works of “Jigoemon Buddhist Altars”, still being kept today in many a household.

Tokuga gifted the world with a legacy of highly delicate and refined works. For example, the “Set of Nine Flowers and Birds Wedding Sake Cups” are adorned with superb drawings, achieving overall elegance and sublime beauty. Whereas the “Flowers and Birds Document Box” (Tokyo National Museum collection) proudly displays an extravagant look constructed by precise application of techniques for combining gold maki-e and inlays.

Hakucho produced many fine pieces that could be seen in various exhibitions from time to time. Most notable instances include Kyoto United Competitive Exhibitions (1888), the Fourth National Industrial Promotional Exhibition, the Exposition Universelle of 1901 in Paris, as well as the Saint Louis World Fair in 1904, having won awards in all of the listed events. He moved to Kanazawa in his old age.

Jigoemon XIII, Tameji learnt maki-e from Hakucho, but he moved to Kyoto in 1925 and worked there as an embroiderer, temporarily suspending the succession of Jōhana Maki-e.

In order to revive the severed succession of Jōhana Maki-e, Jigoemon XIV (Hakusho) went to the Kyoto Senior High School of Arts to study lacquering, and then became an apprentice of Kyoto maki-e under Chokan Ema. After coming back to Jōhana in 1947, his first creation for the revival of the family trade was a piece submitted for imperial appreciation. In the following year (1948) his “Mandarin Duck Box” was nominated for the fourth Japan Art Academy Awards,

proving once and for all the staying power of Jōhana Maki-e. Moreover, Hakusho tackled new themes never explored in Jōhana Maki-e before, and developed new directions for expressions. He also vigorously worked on the repairs of Hikiyama Festival parade floats, cultural assets used in the Jōhana and Yao based event, and worked diligently on exhibitions of work of the previous generations of the family. After his death, Jigoemon XV (Yoshihiro) and Jigoemon XVI (Yoshitomo) followed in his footsteps.

Jōhana Maki-e began with the revival of Mitsuda-e, which laid the foundation that white maki-e was created upon, each successor of the Ohara family continued to add innovations to their creations according to their own artistic sense, and all such developments are passed down from generation to generation. Not even the drastic changes in the society brought about by the Meiji Restoration or the World War could disrupt the continuation of the family tradition, which is a most unusual exception in the world of fine and applied arts.

Reference

Jigoemon and Jōhana Maki-e (Tetsuji Suzaki)

History and culture of Jōhana (Jōhana Education Committee)

@jigoemon16

© Jigoemon Ohara All rights reserved.